Back in May I was kindly invited to speak about the wonderful Cornish ancient sites on Bodmin Moor and the research I have been doing into the relationship they have with the sky. Here’s a link to the talk,

Back in May I was kindly invited to speak about the wonderful Cornish ancient sites on Bodmin Moor and the research I have been doing into the relationship they have with the sky. Here’s a link to the talk,

Were the holed stones a cosmological calendar?

Written after the April 2023 archaeological investigation of the stones

Adjoining the ritual landscape of Tregeseal near St Just, Cornwall lay a curious collection of stones known as the Kenidjack Holed Stones, which are named after the common land on which they are sited (Latitude 50.1360°, Longitude -5.6537°). The site consists of four large granite slabs each perforated with a circular hole currently positioned in a row with an ENE-WSW orientation of 67°, with a further fifth smaller holed stone a few meters to the NW of the main row. The stones are distinctive due to being a collective group with holes, and while there are other examples of holed stones in west Cornwall (including a number near the Merry Maidens stone circle), it is unusual to find a group of them together. It is considered that they are most likely a collected monument which relates to the local Bronze Age barrows, stone circles and other monuments within the immediate location. They were drawn in 1842 by John Buller laying prone on the floor.[1] All the stones have likely fallen and been re-erected a number of times. In 2020 one of the stones became loose and fell over, the hole in which it had sat was very shallow and although it was propped back up it needed to be reset in the ground in a more robust manner. By 2023 a second stone was also becoming loose and this led to the opportunity to examine if there was any evidence of their original positions in the ground immediately surrounding them or if these had been lost. The archaeological investigation was led by Peter Dudley of the Cornwall Archaeological Unit with support from Laura Ratcliffe-Warren and a team of volunteers from the Penwith Landscape Partnership. Historic England grant-funded the work as part of the monument management programme of conservation works.

The monument consists of the four larger stones in the row and a further outlier stone to the main row. The stones in the row have been called A-D for the purposes of this investigation (with E being the outlier). Three stones in the row are upright while the fourth lays prone and broken with only half of its hole still visible (as it was drawn in Buller’s early sketch). The smallest holed stone is an outlier to the NW of the row and has likely been moved from its original position and re-erected with a viewpoint of the outcrop of the top of Carn Kenidjack in mind. It was photographed in 2010 broken in two and has been reset in its current location.[2]

Image: Stone Row with each stone labelled from A – D

Credit: Carolyn Kennett

Stone A and Stone C were subject to the archaeological investigation conducted over two days in late April 2023. Two separate 1.6 x 1.2m trenches were opened up in the immediate area around stones A and C before both were replaced in the same position as before the conservation works. In an effort to make stone C more secure it was reset with its long edge into the ground and short square edge at the top. The chosen side being matched to Charles Henderson’s 1922 drawing of the stones.[3]

Image: Stone C following the 2023 conservation works

Credit: Carolyn Kennett

There was no evidence of any original setting or ground disturbance relating to Stone C. In Charles Henderson’s drawing, he has this stone positioned closer to Stone D and this could be the reason that no ground disturbance was found.

Beneath the location of Stone A the team uncovered the edge of a possible large pit or hollow, with a fine greasy layer at its base. From its texture, the layer was possibly organic-rich in its composition. Within this was a discarded rough flake of flint (also burnt), knapped off from the outer edge of a flint nodule. It is difficult to date the pit/hollow, especially considering the later changes to the monument. It could potentially date from the erection of the monument and perhaps indicate that there was a fire in the vicinity of the stone, however, without full excavation, a fuller understanding is difficult to establish. Care was taken not to change the orientation of the stones although Stone A was buried approximately 20cm deeper than it had previously been to ensure its long-term stability.

It was concluded that the monument had undergone disturbance in both orientation and original positioning of the stones. The earliest description of the stones has them positioned in a line and there is nothing to suggest they would have stood in any other way. The 2023 archaeological investigation found little indication of their original position. Therefore the following is a suggestion of what may have proved interesting about the holes and related skyscapes at the site during the Bronze Age, rather than a definitive conclusion about the orientation of the stones, holes and related skyscapes. This examination tentatively discusses the possible role of the holes in their relationship to the cosmos while taking into account the challenges of orientation.

Looking directly through the holes

Image: Sunrise through stone D, 17th December 2021

Credit: Carolyn Kennett

The stones are located on the side of an eastern slope leading up to Carn Kenidjack and keeping this feature in sight at the monument may have been important in the choice of location of the row. Each hole is positioned low on the stone and the rise in slope makes it impossible to observe the sky when looking towards Carn Kenidjack through the holes, and you can’t see the sky in this direction. Looking through the holes in the opposite direction gives a slightly different view of the southeast horizon, as the stones are each positioned at a different angle in the row. Due to the aspect of the site and the rise in slope, it makes more sense that any observations of the sky made through the holed stones would be limited to this general direction. The current orientation gives sightlines through the holes with azimuths between 105° and 135°. This relates to rising objects of the celestial sphere and it is possible to see the sun, moon and a number of stars in this direction as they move through their celestial cycles. The stones could have been orientated to watch for seasonally important sun and moon rises or helical-rising stars maybe marking chosen calendrical events.

Image: Horizon positions which are observable through the holes (pre-archaeological investigation)

Credit: Carolyn Kennett

Image: Profile of horizon (horizon scale exaggerated x7)

Credit: Graphics by HeyWhatsThat

After the investigation, Stone D’s orientation to the furthest southeast part of the horizon remains unchanged. Stone C was orientated towards the ESE, resetting the stone hasn’t changed this orientation by much and it still faces the lower ground between the two ridges on the horizon.

Image: Horizon view through Stone C following the 2023 conservation works

Credit: Carolyn Kennett

Stone A is orientated centrally of the three. This orientation changed little after the stone was reset and still was centred on the distant southeast ridge. When looking directly through the holes at the horizon there is a crossover with Stone C and D’s views.

Image: Horizon view through Stone A following the 2023 conservation works

Credit: Carolyn Kennett

The sun and the holes

The sun changes its rising position throughout the year, rising directly in the east at the equinox and furthest to the northeast for the summer solstice while rising at its furthest point to the southeast at the winter solstice. If the stones were orientated in the way they are today there would have been times when the sun would rise and shine directly through the holes. Could the holes be used to observe the rising sun through them?

Image: Sunrise through stone A, 1st December 2019

Credit: Carolyn Kennett

The location of the holes low to the ground gives an uncomfortable observing position and looking directly at a rising sun is fraught with danger as the sun can cause serious damage to the eyes. There is an alternative way in which the sun, hole and stone could work in unity. Instead of looking directly through the hole, an observer waits until after the immediate sunrise for a shadow to form behind the stone. The shadow only takes minutes to form after sunrise and if the stone is orientated to a corresponding part of the horizon where the sun rises a beam of light shines through the hole onto the ground.

Image: Sunrise through stone A, 6th December 2020

Credit: Carolyn Kennett

The rising sun will form a circular sun beam onto the stone’s shadow. The connectivity between the sun, stone and shadow may have been of interest to the people who created the holes in the stones. As a phenomenological effect, it could have been perceived as a mastering of the sun itself (a possible deity) by casting it down, bringing it to earth while shrinking it and harnessing its power and warmth at ground level. I can speak from experience when I say that the concentration of sunlight shining through the hole is a great way to warm your hands on a cold morning! Alternatively, It could have been seen as a demonstration of light overcoming darkness, with the sunbeam forming centrally in the dark shadow behind the stone.

Image: Sunbeam shining through the hole captured onto a piece of card

Credit: Carolyn Kennett

The sunbeam is an ephemeral, time-sensitive feature. It would only be visible within the shadow for a number of consecutive days, for a few minutes at a time. All the holes are of similar diameter and in theory this would allow the holed stones to be used as a rough calendrical device from the number of days the sun would shine through the hole. If the holed stones were standing similarly to their current positions then each hole aligns with a different set of sunrises which partly overlaps because of the view of the horizon through the holes.

The angular diameter of the sun, corresponding hole and distance to the eastern horizon means that the sun would shine directly through the holes for approximately 20 consecutive days (there is some discrepancy in this as the daily displacement of the sun is not uniform during the solar year). In their current positions Stone C correlates to the sun rising from early November to late November, stone A corresponds to dates from late November to mid-December and Stone D relates from early to late December including the rising sun at the winter solstice. There is a large crossover in dates between Stone D and Stone A and the people who positioned the stones may have purposely made the sunbeam shine through multiple holes with the overlapping highlighting more significant dates.

Stone B may have filled in the gap in sun beams and acted as a midpoint between Stones C and A. Stone D’s orientation includes part of the horizon which is too far south to see the sunrise during the annual cycle. In its current position, the rising winter solstice sun would be a central feature to the hole. It is unlikely we will ever know the orientation of stones but if they are any way similar to their position today they could have acted as a calendar and functioned (with the other prone stone) as a countdown signal perhaps to the winter solstice,.

Image: Sunrise through Stone C, 1st December 2019, at this angle the sun no longer shines all the way through the hole

Credit: Carolyn Kennett

The first linked sunrise would occur around the cross-quarter period known as Samhain and a time to harvest, while the final holed stone is centred around the time of winter solstice when the sun reaches its most southerly position. The holes would unlikely have been used as an accurate dating tool, instead, it could have been a method of honouring the importance of the sun at this time of year. Capturing and ground casting the sun during the darkening of the seasons could have been seen as significant. The other monuments in the immediate locale have connections to the winter solstice festival. Tregeseal passage grave in the valley below is orientated to the winter solstice sunrise and contained a cross-based urn linked to solar symbolism.[4] Furthermore, the Tregeseal stone circles are focused on a sea gap which incorporates a liminal view of the Isles of Scilly 26 miles off the coast and the winter solstice sun sets in that direction when observed from the circles. Locally the Neolithic Chûn Quoit has an alignment to Carn Kenidjack suggesting this was a longstanding important location to mark the winter solstice.[5]

Observation of light beams in shadows allows people to observe the sun indirectly, while not hurting the eyes as would occur with direct observation, much the same way pinhole projection is used today within astronomy. This method may have been used at another holed stone in Cornwall, through the hole in the capstone at Trethevy Quoit. When the sun reaches its zenith during the summer months it rises high enough in the sky to shine directly through the hole casting a sun beam onto the ground below. This occurs on the summer solstice at noon (UT).

In theory, the full moon could work in a similar way to the sun, shining moonlight through the holes onto the shadow behind the stones and could relate to different full moons as it moves through its phase cycle. The full moon is working in opposite to the sun, being reflected sunlight, so the time of year it would be shining through the holes at full would be in the summer months. In many ways, the full moon in the summer months is less significant than that of the winter full moon. The daylight hours in the summer are much longer and the full moon rises and sets low in the southeast making less of a visual spectacle than in the winter months. It is not rising high like in the winter months, where the full moon played a role in bringing more light to dark nights. At the holed stones latitude of 50.136°, there is little astronomical darkness around the summer solstice and the moonlight would be diffuse and dim and unlikely to cast a moon shadow or light through the hole. It seems more likely that the rising sun would be visually impactful and significant.

Helical-rising stars and seasonal timing

Helical-rising stars have been used in many societies to set dates and festivals. This is a significant moment when a bright star can be seen rising in the morning for the first time before dawn light drowns it out. The motion of the Earth means that stars are seasonal and they rise approximately 4 minutes earlier each day. At times of the year, certain stars are not visible and their return to the night skies can herald the start of a season. The return of Sirius to the skies was used in such a manner by Ancient Egyptians, while the star group the Pleiades were used in this way in Ancient Greece.

The stones could have been positioned to watch for certain helical bright stars rising. This would involve the observer laying prone observing the night horizon directly through the hole. The horizon in this direction is fairly uniform, it has an elevation of 1.2-2.2° above 0. As the stars would be observed low to the horizon a person would be looking through a thicker layer of atmosphere and the light travelling from the stars would be scattered making them hard to see. Therefore only the brightest of stars would be observable at these low elevations. The holes could in effect help by limiting the view. If you hold up your hands in front of you and form a circle in which to look through you will note that you are narrowing your perspective to a more focused view, it’s an optical illusion but could aid with sharpening the view. Looking through the holed stones creates the same effect as you narrow your worldview. The only stars visible would have an apparent magnitude 1.5 and brighter. Star’s positions change due to precession. For instance, the bright star Sirius would rise at this latitude with an azimuth of 125° in 1500BC and 131° in 2500BC, as there is no accurate date from the monument this means that stellar objects over a wide range of declinations have to be considered.

The holes correspond to a horizon range which covers the rising positions of celestial objects with declinations between approx. -10° and -35°. Following is a table with bright stars observable at this latitude. The yellow highlighted ones have orientations which correspond and could have been seen to rise within one of the holed stones during the early Bronze Age period of 2000BC.

| Star | Apparent | Declination | Declination | Declination | Declination | Declination | Right ascension |

| Name | Mag. | 3000BC | 2500BC | 2000BC | 1600BC | J2000 | J2000 |

| Sirius | -1.46 | -22°21’15” | -20°42’47” | -19°16’55” | -18°17’55” | -15°25’28 | -18°17’55” |

| Arcturus | -0.04 | 48°33’57” | 45°44’31” | 42°47’42” | 40°22’44” | 21°24’54” | 14hr21m0s |

| Vega | 0.03 | 43°59’58” | 42°36’06” | 41°23’05” | 40°32’46” | 38°26’25” | 18hr36m20s |

| Capella | 0.08 | 26°10’08” | 28°53’10 | 31°33’38” | 33°38’33” | 46°26’38” | 5hr15m40s |

| Rigel | 0.12 | –25°37’54” | -23°04’02” | -20°37’32” | -18°46’39” | -8°12’04” | 5hr14m31s |

| Procyon | 0.38 | 2°58’48” | 4°31’55” | 5°49’32” | 6°39’36” | 6°15’46” | 7hr42m56s |

| Betelgeuse | 0.5 | -7°27’02” | -4°57’60” | -2°38’03” | -0°53’50 | 7°23’45” | 5hr55m1s |

| Altair | 0.77 | 9°58’52” | 8°34’10” | 7°25’26” | 6°42’35” | 8°28’33” | 19hr48m0s |

| Aldebaran | 0.85 | -4°46’48” | -2°02’23” | 0°39’18” | 2°45’17” | 16°42’25” | 4hr35m35s |

| Antares | 0.96 | -4°08’35” | -6°55’16” | -9°40’28” | -11°50’08” | -26°24’23” | 16h29m26s |

| Spica | 0.98 | 14°42’23” | 12°35’39” | 10°16’60” | 8°18’55” | -11°07’23” | 13hr25m24s |

| Pollux | 1.14 | 22°51’10” | 24°49’07” | 26°31’51” | 27°41’40” | 28°11’30 | 7hr48m56s |

| Fomalhaut | 1.16 | -43°58’06” | -44°11’06” | -43°57’28” | -43°27’45” | -29°25’25” | 22hr55m50s |

| Deneb | 1.25 | 36°30’34” | 36°28’47” | 36°39’38” | 36°57’23” | 45°16’43” | 20h41m25s |

| Regulus | 1.35 | 23°36’39” | 23°55’41” | 23°52’48” | 23°34’45” | 11°54’50” | 10hr09m41s |

| Adhara | 1.5 | -33°38’01” | -32°09’34” | -30°53’29” | -30°01’54” | -28°58’24” | 6h58m36s |

| Castor | 1.57 | 24°51’48” | 27°00’26” | 28°54’51” | 30°14’31” | 32°04’45” | 7hr35m40s |

| Pleiades | 1.6 | 0°05’22” | 2°49’59” | 5°36’07” | 7°48’42” | 24°22’03” | 3hr45m49s |

Only three stars are considered to be close matches to the holes, these are Sirius, Rigel and Adhara and due to the little correlation between the brightest stars in the sky and the position of the holes, it seems very doubtful that they were used to observe helical rising stars.

To conclude, if the holed stones were used as observational tools the most probable method would be linked to viewing the sun. It seems most likely that the best method for doing this was watching for the beams of light to be cast through the holes made by the rising sun. It’s dramatic watching the beam of light illuminate the shadow cast by the stone and I really recommend getting up on a winter’s morning to witness this if you get the chance.

Image: Sunrise 17th December 2020

Credit: Carolyn Kennett

[1] Buller, John (1842) A Statistical Account of the Parish of St Just in Penwith in the County of Cornwall. Dyllansow Truran p. 100

[2] https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1006755?section=comments-and-photos

[3] Charles Henderson’s 1922 sketch of the stones (taken from the 2011 report on the conservation works to the lone stone – Preston-Jones, A, 2011. Kenidjack holed stone, St Just, Cornwall – repair and restoration. Truro: Cornwall Archaeological Unit, 2011R119)

[4] Kennett, Carolyn (2021) Burying the Sun, Crossed Based Urns and Solar Symbolism. Astronomy Yearbook, White Owl Press. p 152.

[5] Kennett, Carolyn (2021) Tregeseal Circles and the Solstice Sun. Meyn Mamvro Vol 2. No 3. pp.8-10.

On summer solstice eve I was able to photograph the alignment between the circle and the setting sun over Brown Willy and the setting sun lines up well with the prominent hill. Even taking into account that in prehistory the sun wouldn’t set in exactly the same position today (it would be 2 solar discs to the right in the photo above) there is a clear correlation between the two.

Craddock Moor circle isn’t the only prehistoric site where you can watch the summer solstice sunset over Brown Willy and there is an extended line of monuments across the moor where this can be seen. These include the standing stone above the Hurlers and at Goodaver circle.

Craddock Moor circle has another alignment this time with the rising summer solstice sun and Stowe’s Hill. The winter solstice sunrise and sunset have a loose arrangement with the barrows on Caradon Hill and a rolling sunset down Tregarrick Tor. This makes it a very remarkable solstice-aligned circle.

On solstice eve I was treated to sun dogs forming either side of the sun which was a magical sight which kept me watching the skies before the sunset.

Please be aware that Goodaver Circle is on private land and permission must be sought before visiting it.

Within the digitised Stanley Opie collection of photographs at Penzance’s Morrab Library, three images bear the title “Unidentified stone circle. Possibly on Bodmin Moor.” These photos initially evoke the essence of a typical Bodmin Moor circle akin to the Stripple Stones, nestled in expansive moorland with panoramic vistas.

Stanley Opie, an archaeologist with a penchant for capturing historic sites and archaeological excavations in Cornwall, was born in Barncoose, Redruth, in 1884. Armed with an Ensign Cameo No. 2 camera and Imperial Eclipse plates, he documented these sites from 1930 to 1950. The Morrab Library in Penzance now houses its comprehensive collection, which has been meticulously digitized and is accessible online and through authorized visits. Throughout his career, Opie photographed numerous locations in Cornwall and beyond, presenting a formidable challenge in identifying the locales depicted in his images.

Closer scrutiny of the three images confirms their association with the Goodaver stone circle on Bodmin Moor. This revelation may surprise observers, as a contemporary visit to the site reveals a markedly different landscape. Presently surrounded by trees from a local plantation, the circle’s original context is obscured. However, this wooded enclosure provides a tantalizing glimpse into the potential positioning of the circle and its conceivable sightlines. Such insights allow us to speculate about astronomical alignments that may have held significance for the circle’s original builders.

In the current era, the entire site is enveloped by trees, except for a western view that descends to the farm and riverbed below. An opportunity arose to capture the site before aligning Opie’s photos with the landscape features, offering a unique perspective on the possible sightlines that the original builders may have considered when siting their circle, unobstructed by the present-day vegetation.

The Rabbit stone helped orientate the circle in the photos (to the left of the image

It helped that there were several unusually shaped stones. One in particular got named the rabbit stone after having a similar profile of the Lindt rabbit, it can be seen on the left of this image. (I should say at this stage that the circle was heavily restored in 1906 and some of the stones are thought to have been replaced incorrectly, even upside down).

Opie Photograph no 1

This image took a bit of matching. The two central blocky-looking stones and the rabbit-shaped stone on the right of the image helped orientate it. In my image below the rabbit, the stone is also to the right and slightly obscured by the rocks in front of it.

The rise in the ground beyond the circle is Brown Gelly, which is towards the southwest. This Tor is obscured by the trees on the left of the more recent image. The area has several interesting ancient sites on it including some Cairns on the top, which can be seen on the ridgeline of the image. There can be no solar or lunar alignment with these local cairns as they are too far to the south when standing within the circle.

Stanley Opie, “Unidentified stone circle. Possibly on Bodmin Moor,” Morrab Library Photographic Archive, accessed January 4, 2022, http://photoarchive.morrablibrary.org.uk/items/show/6371

Image 1 match

Opie Photograph number 2

This second image gives a more expansive view looking out from the circle to several ridgeways and hills beyond.

Looking at the stones in the image, the tall pointy stone and gap next to the man at the front of the circle helped orientate the image, as did the rabbit-shaped stone behind him. The image looks from the south of the circle facing north.

The hill towards the centre-left of the image is Leskernick, Bronn Wennili (Brown Willy) may be visible to the left of the image. This is exciting as it means that standing in the circle you could have seen the summer solstice sunset over the distant hill. This is an extension of the line which starts at the newly discovered menhir on the ridge above the Hurlers Circle, extends through Craddock Moor Circle and the avenue at Craddock Moor, and onwards to Goodaver Circle. Making it possible to see the same summer solstice sunset at important prehistoric locations across the moor.

Continuing to the centre-right of the image is the local plantation ridge. Fox Tor which is relatively local to the circle would have been to the right of the image.

The pointed stone that the man is standing beside in the Opie image is front left in the recent one. My image is orientated slightly differently from the old image. It would have been pointing directly down the field to the right of the modern image. Looking down the neighbouring field in recent times there is no possibility of seeing what hills lay beyond.

Stanley Opie, “Unidentified stone circle. Possibly on Bodmin Moor,” Morrab Library Photographic Archive, accessed January 4, 2022, http://photoarchive.morrablibrary.org.uk/items/show/6370

Image 2 Match

Opie Photograph no 3

The Opie photo shows stones in profile against the sky above with no plantation beyond, the rabbit-shaped stone is in the front row of the circle on the central left. Matching it to my photos of the circle, it has been taken from the northwestern side of the circle down the ridge a little way. Kilmar Tor would have been visible if the photo had been taken with slightly increased elevation. This Tor is directly east from the circle and in the position of the rising sun at the equinox (midpoint between the solstices). The modern photo has been taken from higher up the hill and the craggy tops of Kilmar Tor can still be seen through the gaps made by the less dense boundary of trees.

Stanley Opie, “Unidentified stone circle. Possibly on Bodmin Moor,” Morrab Library Photographic Archive, accessed January 4, 2022, http://photoarchive.morrablibrary.org.uk/items/show/6372

Image 3 Match

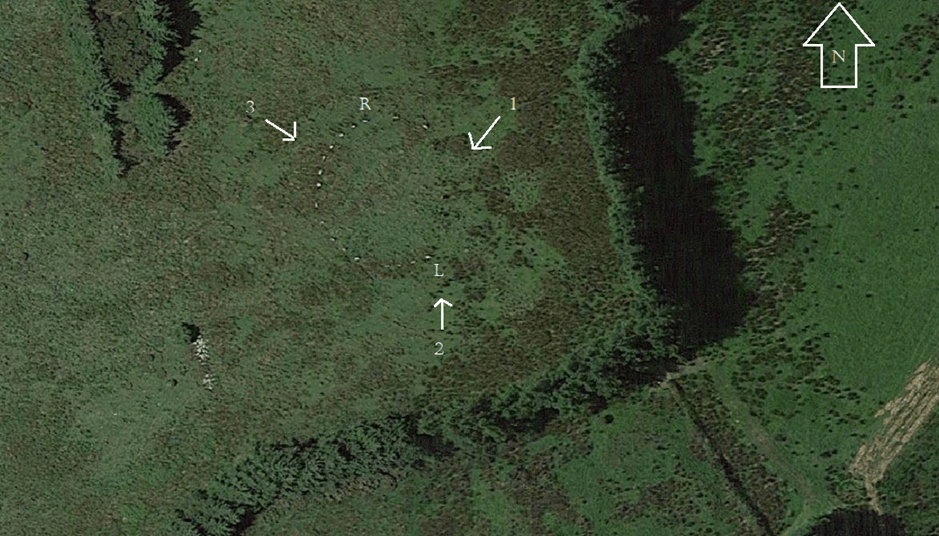

A plan of the matched direction of the photographs taken by Opie numbered 1-3

From matching the photographs old to modern I was able to make a plan of the directions which the Opie images were taken: The plan below is as follows:

R = Rabbit stone

L = taller long stone

Credit: Annotated Google Maps image

Finally, I should add that within the Opie photographs, none were taken in the direction of Hawks Tor in the west. This has been identified by Cheryl Straffon and John Barnett as an equinox setting position when standing in the circle. When visiting the circle in more recent times the Tor can still be seen in the gap made by the plantation to the west and is the one remaining solar alignment that could be viewed in action. Maybe one day the larger plantation trees will be replaced with smaller saplings and make the other viewpoints possible.

Access to the Stanley Opie collection and all the other wonderful historic digitalised images that the library has can be made here:

First appeared in Meyn Mamvro Issue 100, First Series, Winter 2019

https://www.meynmamvro.co.uk/archive/

The importance of the Sun has been recognised throughout history. This luminous body defined the lives of people it shone on and the clocklike regularity of its rise and the set was well understood by humanity. Due to its significance symbolic representation of the Sun stretches far back into prehistory. Designs including the Sun weren’t uncommon and by the Bronze Age examples of solar symbolism are found across a range of mediums. Drawings and designs were often abstract in nature. Representation included circles, waves and cross shapes. The cruciform shape in particular has been linked to the Sun by Mary Cahill (2015) and her work on Irish Sun discs. These are flat circular objects made of gold, designed to shine brightly when sunlight radiates onto them. The etching of a cross on the surface shows the rays of the Sun in a conceptual way, maybe representing various solar events such as; Sundogs, pillars, rays and halos. Although no Sun discs have been found in Cornwall, these golden objects have also been linked to the lunula. A lunula was found with a pair of Sun discs in Coggalbeg, Co Roscommon, confirming an association. Furthermore designs on lunula lend themselves to observation with sunlight. There are examples of lunula found here in Cornwall and if you get the chance it is worth visiting the Penlee House Gallery where the Penwith Lunula is on display.

Sun discs with cross-shaped designs were found at Tedavnet, Co. Monaghan Ireland. Image Credit: The British Museum.

Other objects discovered in Cornwall from this period incorporate a cross design. Although perhaps not as glamorous as a golden disc, local urns can include a similar decoration. Trevisker style urns are a design of urn which are predominantly found in the South West of the UK. Dating from the Bronze Age the style is known for its hash/dash and zig-zag lines and use of local materials such as gabbroic clay from the Lizard peninsular. On occasion, the urns have a cross or cruciform design within the interior of the base. This seems to be a rare occurrence but there have been examples of cross based urns found at the Trevisker village excavation, Boleigh barrow, Tregeseal chambered tomb and an example from further afield in Kent. This final example was placed in a ring ditch, and the soot recovered from inside the Urn was radio carbon-dated to 1600-1320 cal BC. It was found shattered into over 200 pieces but was reconstructed, with its internally crossed base being clearly observable.

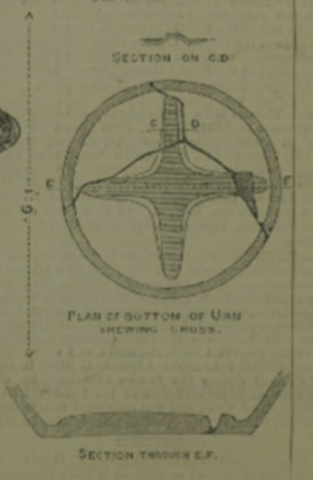

The urn from the Tregeseal chambered tomb was recovered by William Copeland Borlase in 1879. Found at the end of the passage, in a separate area, it was recovered almost complete by Borlase during his excavation. It now resides within the British Museum. Tregeseal Chambered tomb is part of a group of Bronze Age entrance graves in Penwith which include Bosiliack, Tregiffian and Pennance. As an aside radiocarbon dating results on a burial at Bosiliack gave 1690-1510 cal BC (Jones, A and Thomas, C. 2010) a similar date to the urn found in Kent. The Tregeseal urn is a large example and is 21 inches in height. The Cross shape was meticulously drawn in plan form at the time. The plan was reproduced in the London Illustrated Times and it can also be seen on the wall of the Penlee House Gallery Museum in Penzance.

Trevisker Urn from Tregeseal. Image Credit British Museum Collection Online.

The cross itself would not be integral to the structure of the urn. There seems to be no practical explanation as to why an urn of this size would have this addition in the base. It is therefore interesting to consider if some Trevisker urns could be following the tradition of Sun discs and offer a design that is indicative of solar symbolism? One aspect which strengthens the case of this idea is that the Urn would have started as a disc shape on which the cross shape would be added. Then the sides would have been added to the urn creating the final vessel. Looking down from the mouth of the urn it would have clearly taken on representation of the Sun in a similar way to the Sun disc design. An alternative explanation has been offered by Kavanagh, R (1973) who suggested that the cross was added to demonstrate a bottom of a basket and was a nod to the basketry traditions of the period.

The Tregeseal Urn base – in plan.

Image credit: Report by W.C Borlase circa 1879

The Tregeseal example was discovered within the tomb base up, containing cremated remains. So the cross would have been above the remains. This could have been intentional. Many funerary urns are found base up. A cross at the top could represent a number of ideas. A Sun in the dark? A route to the heavens? A set Sun? There was just one time of the year which the Sun would shine down the chamber to its rear. This was the winter solstice sunrise. A recent survey undertaken by Carolyn Kennett and Grenville Prowse supervised by Penwith Landscape Partnership archaeologist Jeanette Radcliffe found the passage to be orientated at 128degrees. This orientation towards the solar extreme of winter solstice sunrise is in common with local tombs at Bosiliack and Pennance. On this day the sunlight would shine down the passageway hitting the back upright stone at the rear. The urn was positioned behind this back stone in a separate area or cist. Although currently it is difficult to understand the full design of the tomb, as this rear section has been removed and our understanding is reliant on the original plan from the Borlase excavation. It is also worth considering if the positioning of the urn in a separate section was intentional? This position would ensure that no natural sunlight would reach the urn at any time. The symbolism may have shown that it was providing its own light, even on this important day of renewal in the solar calendar.

A photograph taken by Gibson and Sons at the time of the excavation shows a possible blocking stone at the start of the passageway, which would have further limited light down the passage on the solstice. There is no evidence remaining of this stone now, so it is difficult to understand the overall effect this would have had on limiting light at the solstice. It is worth remembering that the final resting place of this urn probably came after a life of servitude. The urn in Kent had traces of animal fats within it and was probably used as a transportation vessel for food before its final role as a funerary urn.

Trevisker style urns are not the only vessels to include crosses on their base. Although in general this cruciform addition to urns is rare and seems to be reserved for the more decorative funerary examples. Other examples of cross based urns have been found in Ireland, Scotland and Yorkshire.

As a final thought, I doubt we shall ever know the full truth behind this oddity in the design, but it is a nice idea to consider that the cross was added by our ancestors to bring light to the darkest of places.

Cahill, M. (2015) Here comes the Sun – Solar symbolism in Early Bronze Age Ireland. Archaeology Ireland 29(1), 26-33,, 2015.

Jones, A and Thomas, C (2010) Bosiliack and a reconsideration of Entrance Graves. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society. 76, 2010, pp 271-296.

Kavanagh, R (1973) The Encrusted Urn in Ireland, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature, Vol. 73 (1973), pp. 507-617

By Carolyn Kennett

First published in Meyn Mamvro 95 (Spring/Summer 2018) and still can be read in the collected works Watching the Sun Booklet by Meyn Mamvro and Mayes Creative (2021)

Boscawen-ûn summer solstice sunset (Credit Carolyn Kennett)

During the last few years, in many ways, Boscawen-ûn became a second home to me. While waiting for sunrises and sunsets I observed the change in the seasons at the circle, all accompanied by the changing looks, sounds and smells. But one thing remained the same and that was the tranquillity of the site. I kept some strange hours, as I was mainly there for sunrises or sunsets and quite often at night. More often than not I was alone in the circle, sometimes for hours on end. One of these visits, in particular, comes to the forefront of my mind. Having risen when it was still dark, I drove to the circle with the beginnings of dawn, hoping the low developing horizontal cloud would clear. I arrived in time for the sunrise of the 25th June 2016. The week had been wet and the solstice had passed behind a thick blanket of cloud. I stood atop Creeg Tol willing the low bank of clouds to blow out of the way, even though I knew I was nearly a week late to see the summer solstice sunrise. The vantage point of Creeg Tol meant that I would see the Sun peer above the horizon, something that I could not replicate in person in the circle below due to the large hedge obscuring this direction. The dawn had a stillness about it which makes it one of my favourite times of the day. The clouds were starting to disperse and right on schedule, the Sun started to peer above the horizon, accompanied by the mixed dawn chorus of birds, roosters and cattle. I photographed the sunrise from my vantage point at Creeg Tol and set off down the hill towards the circle. About halfway down into the hill I started to lose the sunrise, the Sun was setting behind the hill it had just risen from. By the time I reached the circle the Sun was once again well below the horizon. I realised that without the hedgerow I could witness the Sun rising twice, in effect a double sunrise. Once from atop Creeg Tol and then again from inside the circle. I hoped this would work in reverse: with the Sun setting visually from the circle and once again from Creeg Tol. It was an idea I would test out repeatedly over the summer months with great success. I think this double sunset and sunrise during the summer months is one of the most visually beautiful aspects of the circle. A local settlement Goldherring, which has some Bronze Age round huts is north of the site and people could have accessed the circle from the direction of Creeg Tol. Double sunsets and double sunrises are something that we can all witness from the site and this is only the beginning of what makes Boscawen-ûn astronomically special.

It is important to consider Boscawen-ûn in the landscape as holistically as possible. During this project, I wanted to consider the way the circle sat at the base of the northern hill, in what would have been a marshy area and quite possibly difficult to get access to, particularly at wet times. Why had it been positioned here? What would have been seen in the sky? It was equally important to view the site as a part of a changing landscape, where man has shaped and changed the site itself over a large period of time as well as the surrounding landscape. I am a great believer in looking what archaeoastronomy ideas have been historically suggested about a site. These historic ideas brought another list of questions such as: Is there any truth in a Lunar link at Boscawen-ûn? Does the carving on the back of the central stone light up at summer solstice? These were just the start of a list of burning questions that would keep me returning to the site, making measurements, and calculating positions of celestial objects over the coming year. Hopefully enabling me to answer if the site was built with astronomy in mind.

I started by considering if there were any alignments between the circle and features on the horizon. This meant that I needed to map out all the natural and man-made features which would have been found from the period of the stone circle. This was in itself quite a task. The internet was a wealth of information, but local knowledge from people such as Cheryl was a great help to me. Many local sites such as barrows and menhirs had disappeared and I needed to try to reconstruct where they were as accurate as possible in relation to the circle. My final list identified 48 local features or as I would name them, targets. These targets would then be considered against a number of pre-selected celestial events. If all 48 targets were considered against the chosen celestial events, statistically a match would be highly likely. For instance, if we were to consider the targets located around the site in a circle of 360 degrees. If each target considered covered 1 degree with an error of +/- 0.5 degrees a total of 96 degrees or just over a quarter of our circle would be covered in targets. (The error from this project was set as 1.04 degrees this came from a small amount of measurement error as well as error for refraction, extinction, and parallax). Statistically, this would mean that it would be far more likely for a target to make a match with a considered event. Therefore to make the project more robust I needed to reduce the number of targets. I decided first of all to consider targets that were visible from the site and only targets that sat proud against the horizon. The reduction in targets could have been undertaken in a number of ways but I felt that this made the most robust format for retesting any results. This left me with just 7 remaining targets out of the original 48 to match with my events. These were as follows:

The Lamorna Gap – yes it is just visible from the site through the hedgerows. A smaller sea gap further south to the Lamorna gap, Creeg Tol. A barrow just west of Creeg Tol, Chapel Carn Brea, Boscawen-ûn Field Menhir and finally Bunkers Hill Menhir (East). Once the targets were identified I made on-site measurements of their azimuth and altitude and this was converted into an astronomical declination. Alongside the on-site measurements, I ran a computer program called HORIZON. This also gave me declinations for my 7 targets and it acted as a test of accuracy for the on-site measurement, as well as allowing for reconstruction of the horizon behind the hidden, hedgerow covered NE direction.

Boscawen-ûn Field Menhir, with possible fallen menhir in hedge behind (Credit Cheryl Straffon)

Next, I considered which astronomical events I would examine alongside the targets. I decided to look initially at five events in total. These five events would give 14 positions along the horizon: 7 rising positions and 7 setting positions. These were the extremes of the solar calendar or the solstices, as well as the solar equinox positions. I also considered the lunar standstill positions both for lunar major and lunar minor. I then calculated the declinations of these 14 events for a date of 2500BCE. The horizon position of a solstice Sun and the lunar positions in 2500BCE has moved slightly compared to its current position, whereas the equinox would be in virtually the same place. So a rising solstice Sun would have a declination of 23.9 degrees in 2500BCE whereas it would have a declination of 23.4 degrees currently which is on a flat horizon at the latitude of Boscawen-ûn equates to an azimuth difference of 1.02 degrees.

When all this was considered I could look for matches between my 14 events and 7 targets. I could see immediately that 4 of my 7 targets declinations matched with one of the fourteen identified events, within the limits of the error I had set. The first and probably most primary of these is that an observer in the circle at 2500BCE would see the winter solstice sunrise rising from the Lamorna Gap. The Lamorna Gap at present is obscured by hedgerows, but without this vegetation would have been a subtle sea view at best. The Lamorna gap declination was measured as -23.6 +/-1.04 degrees, matching a winter solstice sunrise of 23.9 degrees. Also, you must consider that the sea view extends for more than 1 degree along the horizon and that this event could be observable over the coming millennia.

This first alignment extends through the circle to my second alignment. This is to a barrow which is no longer visible, it was located to the west of Creeg Tol. It would be in the position of the summer solstice sunset when observed from the circle. It had a measured declination of 24.3 +/- 1.04 degrees coinciding with the declination of 24.9 degrees. Equally an observer at the barrow would have been in a position to observe the winter solstice sunrise out of the Lamorna Gap. Its position just above the circle would give an observer a more advantageous height and a more pronounced view of the winter solstice sunrise from the Lamorna Gap. It is interesting to note that the winter solstice sunset at this time would just fall into the large sea gap at the Tregeseal stone circles. Although at Tregeseal the sea gap is far more pronounced, there is possible that there is a connection between the two sites on this date.

The other two matched alignments came between the circle and lunar major standstill positions. I found that the position of Creeg Tol matched the lunar major sunset northernmost position, it had a measured declination of 28.3+/-1.04 degrees coinciding with an event declination of 28.9 degrees. The nearby Boscawen-ûn Field menhir was the final alignment and it was in the lunar major sunrise position. This had a measured declination of 28.9+/1.04-degrees which coincided with the event declination of 28.15 degrees in 2500BCE. The position of the Field menhir was slightly to the west of calculated declination for the lunar alignment, but it is conceivable that another stone now recumbent in the hedge made a pair and this pair once framed the rising Moon at the extreme of the lunar major cycle. Although we should note here that it may not have necessarily been a full Moon at that time, as the Moon at its standstill declination can be at a number of positions within in its phase cycle.

Lunar standstill links are not well documented in Cornwall. They are considered a feature of recumbent stone circles in East Scotland but have also been found in western Ireland and more recently in western Scotland. The discovery of two lunar standstill points at Boscawen-ûn is both interesting and intriguing; raising more questions than it answers. Boscawen-ûn does have myths surrounding it which are linked to the lunar cycle, so this could be a feature of this site. Future work in west Penwith will consider evidence for lunar links. For instance, the Merry Maidens which I had discounted through my reduction of data, as it did not stand proud against the horizon is in the Lunar Major Standstill Southern rising position from Boscawen-ûn with a declination of 29.9 degrees. This concludes the main horizon findings but as I said I also looked at other features within the circle.

Boscawen-ûn hedge menhir (Credit Carolyn Kennett)

The positioning of the quartz stone to the SW of the circle could signify the start or end of the winter season, but due to its localised vicinity to an observer, it could never pinpoint an actual date, without another position to line it up. The stone on the opposite side could have well been used to align the position but this does not line up with anything calendrically significant. The quartz stone does though align with the cist (located in the NE of the circle) and the out of sight Boscawen-ûn Hedge menhir. The summer solstice sunrise would have occurred along this alignment around 2500BCE. This alignment was first suggested by Norman Lockyer in his consideration of the circle. There is another stone between the Hedge menhir and the stone circle, this would possibly bring inter-visibility between the circle and the Boscawen-ûn Hedge menhir. Even so, there are numerous examples of standing stones being just over brows of ridges that form alignments so this could be a viable consideration when looking at this alignment.

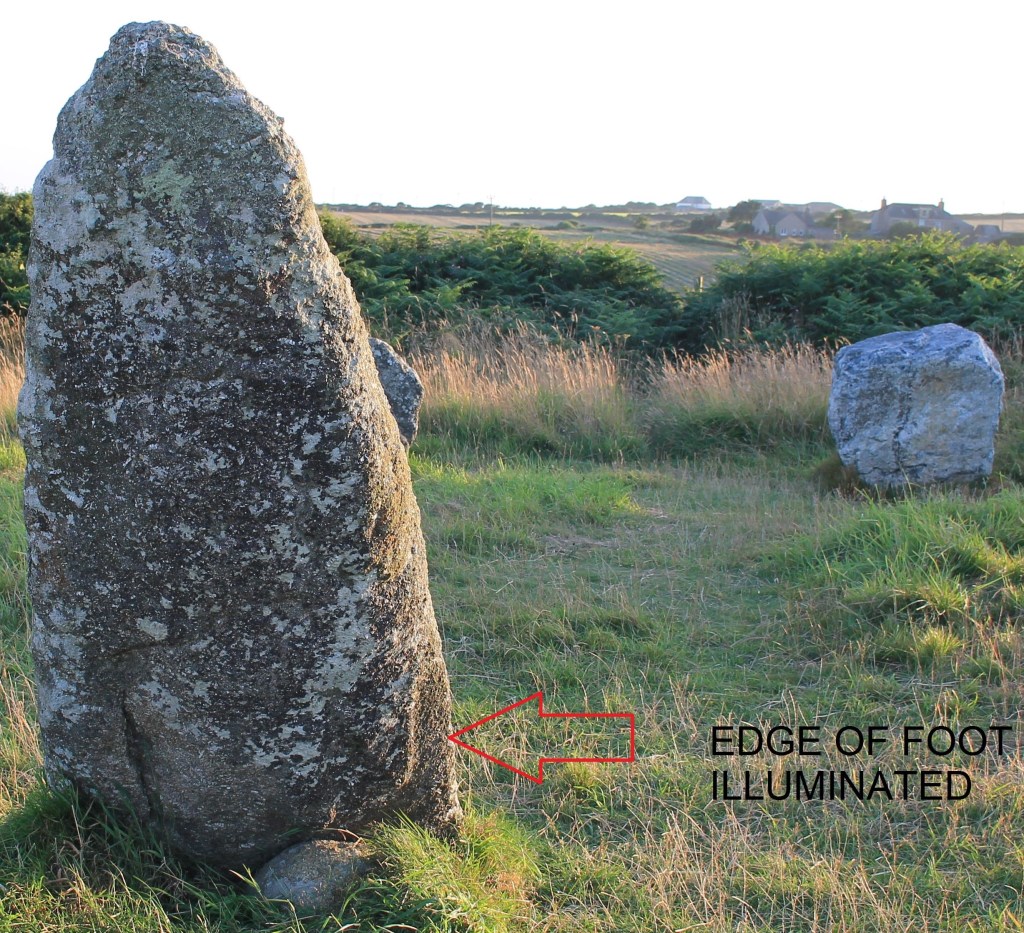

The edge of the foot at the bottom of the central stone is illuminated (Credit Carolyn Kennett)

Rock art carving (or either foot or axes) have been identified on the central stone. I was able to calculate the amount of time the art would be illuminated for in the year 2500BCE. The art on the back of the central stone is only fully illuminated in and around summer solstice sunrise. Without any vegetation, a full illumination would occur for 30 days on either side of the solstice. The maximum time in minutes that the art would be illuminated would occur on the summer solstice. This amount of time would reduce each day until a full illumination could not happen 31 days later. It must be noted that this measurement takes into account a completely flat landscape. Any vegetation would significantly reduce the length of time and amount of days the art would be fully illuminated. Partial illumination of the art also occurs and this time it happens both in the morning and the evening in and around the summer solstice, this partial illumination would occur over a much longer period.

There are many more suggestions that could be made particularly linking stellar events to the site. Without more accurate dating these suggestions must be taken under advisement. For instance, the Pleiades would set over Chapel Carn Brea in 1500BCE but at an earlier date of 1800BCE, it would have set to the south of the framed hill. I did consider if the central stone could have pointed at a star. The only bright star that it could have pointed at was Arcturus and this would have been at a remarkably early date of 3820BCE. This must be taken under advisement, as the stone could have moved over time. Overall the suggestions of stellar alignments without accurate dating are always difficult to suggest. It does seem that a number of astronomical features were considered by the builders of Boscawen-ûn. They certainly had an eye for the solar calendar within the design but perhaps more unusually a knowledge of the lunar cycle. This project, for me, has raised more questions than it answered and I will be continuing it by looking for further examples of lunar alignments within Cornwall and trying to draw more conclusions about the astronomical features at some of the other Cornish circle sites.

More of this story can be read about in my book Celestial Stone Circles of West Cornwall. Which can be accessed here

Having just returned from a trip to St Martin’s on the Isles of Scilly. I thought it would be worth mentioning a couple of interesting rocks that we came across while walking around the Island. I’m always on the look out of these with my partner and enjoy finding natural erratic’s which move (logan stones), or seem to have been propped up by a smaller rock. On this visit there were two of these worth mentioning from St Martin’s and then I also came across another logan earlier in the year on Bryher, while searching for the perfect place to watch the sunset.

The St Martin’s rock which moved when stood upon is found to the northern side of Chapel Downs, a short distance away from the Day Mark and just off the well trodden pathway leading around the eastern coastline. It was positioned near the coastline and a rocky outcrop, large enough to be significant in the landscape, but on a small enough pivot that it was easy enough for one person to rock back and forth.

The propped stone was a mile or so away on the Burnt Hill promontory fort, this one was spotted by my partner as I was looking at a possible entrance grave and a couple of hut circles. A large boulder had what seemed to be a natural split down the centre and one half of the rock had been propped up by a smaller boulder making a gap underneath. Whether this had happened naturally is unknown but a number of props which have had a human hand playing a part have been identified on the mainland.

The final stone worth mentioning was noticed on a trip earlier this year while visiting Bryher. Looking for a perfect place to watch a sunset, this large boulder was on the western side of Samson Hill, overlooking the entrance grave and island of Sampson. The boulder was a large and most likely natural feature about 1/3 of the way down the hill and it seemed to be the perfect spot to watch a sunset from. Climbing onboard the rock itself didn’t noticeably move, but when a second person also scrambled onto sit on the top the stone began to rock back and forth. Not only does the boulder have a great view of an entrance grave underneath it, it also has a wonderful view of the sunset, and I liked to think that people have been visiting and rocking this stone for millennia.

Wandering around Bodmin Moor there are a number of well known viewing frames and propped stones. Positioned on the hilltops and slopes of the better known tors a large number were identified by Roger Farnworth. Articles about aome of these appear in Meyn Mamvro issues 63 and 85. (meynmamvro.com).

Some of them appear to have an astronomical alignment such as the Leskernick Propped stone which has a summer solstice alignment. Many of these frame other hilltops and significant rocky outcrops. Here are two which have not been mentioned by Rogers in the articles.

Garrow Tor prop. Found of the western slopes of Garrow this propped stone frames Alex Tor. Initial assessment shows this to be orientated to the west and Alex Tor would be in the position of the midpoint (equinox) sunset. Prop found by Jamie Ashley.

A second prop on the southern slopes of Brown Willy. This one frames Hawks Tor to the south. There does not seem to be any obvious astronomical connection and the frame points in a just of South direction. Thanks to William Arnold for pointing this one out.

There are lots of props and framing stations to be found in both Penwith and on Bodmin Moor. Other blog posts on this site about these include; Little Galva framing station and Carn Kenidjack propped stone.

On May 29th as part of the CASPN’s annual day of walks and talks I led a walk from Boscawen-ûn following the Trelew line visiting a number of standing stones on route.

The Trelew line was first identified by Sir Norman Lockyer who was considering astronomical alignments from Boscawen-ûn to local features. He suggested the Trelew standing stone was in a November setting position when stood at the circle. Since then John Michel identified an intervening menhir, called Chyangwens, this is found in a local farm hedge. Visible from miles around, it is an impressive piece of granite. Another stone Toldavas extends the line further on from Trelew towards the Lamorna gap on the south coast of Penwith.

When I considered the Trelew line in my work at Boscawen-ûn I felt that it was less likely that it was used as an accurate marker of a solar position. Instead I consider that the stones radiating out from the circle were positioned to lead people either to or from the circle and the Lamorna gap, used as a route for people to travel between the two sites. A similar set of stones also radiate out from the Lamorna gap to the Merry Maidens!!

Why would people want to go to so much effort to mark a way between these two locations? If you are standing at Boscawen-ûn on the winter solstice the sun would rise out of the sea, from a cut in the horizon which the Lamorna gap makes. It is a nice idea to think that people would walk between these locations, maybe in and around the solstice itself. I don’t believe they stopped there, I think they could have continued their journey to Tregeseal to watch the winter solstice sunset in another sea gap. This time one that frames the Isles of Scilly. But that’s a longer story and for another time!!!

Anyway here are some pictures of the Trelew stone and Chyangwens.

Please follow CASPN on facebook or look at their website to find out more https://cornishancientsites.com/

Yesterday the evening had a break in the clouds from the run of stormy weather we have been having in West Cornwall. This gave me the opportunity to get out and try and image the supermoon over an ancient monument. The intention was to image the supermoon at a stone circle so the picture can be used for my forthcoming book on archaeoastronomy and the stone circles in West Cornwall. I knew that Boskednan would give a great horizon for the supermoon to rise above so that became my destination of choice. I knew the moor would be muddy, so I decided to park closer to Men-an-Tol rather than walk in from Ding Dong mine. Although this was a longer walk it would mean that I could also image Men-an-Tol if needed. Wow, I hadn’t expected the whole Moor to be a quagmire – it was virtually impassable in places and perhaps the wettest I had ever seen it.

The picture of Boskednan shows how wet the ground is. The Sun is setting in among the cloud – low in the Southwest. This is near to the position that the sun would set at the winter solstice, over the clearly placed Boswens Menhir. At Boskednan it was obvious that the cloud to the east of the site was pretty thick but above this bank of cloud, there were clear skies forming. As Men-an-Tol is down the hill from Boskednan I decided that this lower altitude may give the sky clearance from the cloud bank. Setting off back down the hill my walking boots decided to give up with the sole coming away from the boot at the toe -(RIP boots you have served me well – travelling mile upon mile over this landscape!!). So, making a decidedly flapping noise in the wet I gingerly set about getting down the hill to Men-an-Tol. By the time I reached this lower circle the Sun had set and the Moon had begun to rise. The Moon closest to the winter solstice sunset rises and sets in its most northerly position it also rises to its highest altitude. As a supermoon (the Moon is at one of its closest position to Earth) it makes it one of the most impressive celestial sites you can see. Unfortunately, the cloud didn’t play ball and I only managed to get glimpses of the Moon rising there is a second image below.